Religion

Related: About this forumIf God Is Dead, Your Time Is Everything

The idea of eternity, Martin Hägglund argues, destroys meaning and value.James Wood. New Yorker May 13 2019

At a recent conference on belief and unbelief hosted by the journal Salmagundi, the novelist and essayist Marilynne Robinson confessed to knowing some good people who are atheists, but lamented that she has yet to hear “the good Atheist position articulated.” She explained, “I cannot engage with an atheism that does not express itself.”

She who hath ears to hear, let her hear. One of the most beautifully succinct expressions of secular faith in our bounded life on earth was provided not long after Christ supposedly conquered death, by Pliny the Elder, who called down “a plague on this mad idea that life is renewed by death!” Pliny argued that belief in an afterlife removes “Nature’s particular boon,” the great blessing of death, and merely makes dying more anguished by adding anxiety about the future to the familiar grief of departure. How much easier, he continues, “for each person to trust in himself,” and for us to assume that death will offer exactly the same “freedom from care” that we experienced before we were born: oblivion.

...

These are visions of the secular. A systematic articulation of the atheistic world view, the one Marilynne Robinson may have been waiting for, is provided by an important new book, Martin Hägglund’s “This Life: Secular Faith and Spiritual Freedom” (Pantheon). Hägglund doesn’t mention any of the writers I quoted, because he is working philosophically, from general principles. But his book can be seen as a long footnote to Pliny, and shares the Roman historian’s humane emphasis: we need death, as a blessing; eternity is at best incoherent or meaningless, and at worst terrifying; and we should trust in ourselves rather than put our faith in some kind of transcendent rescue from the joy and pain of life. Hägglund’s book involves deep and demanding readings of St. Augustine, Kierkegaard, Marx, and Martin Luther King, Jr. (with some Theodor Adorno, Charles Taylor, Thomas Piketty, and Naomi Klein thrown in), but it is always lucid, and is at its heart remarkably simple. You could extract its essence and offer it to thirsty young atheists.

His argument is that religious traditions subordinate the finite (the knowledge that life will end) to the eternal (the “sure and certain hope,” to borrow a phrase from the Anglican Book of Common Prayer, that we will be released from pain and suffering and mortality into the peace of everlasting life). A characteristic formulation, from St. Paul’s Epistle to the Colossians, goes as follows: “Set your minds on things that are above, not on things that are on earth, for you have died, and your life is hidden with Christ in God.” You die into Christ and thus into eternity, and life is just the antechamber to an everlasting realm that is far more wondrous than anything on earth. Hägglund, by contrast, wants us to fix our ideals and attention on this life, and more of it—Camus’s “longing, yes, to live, to live still more.” Hägglund calls this “living on,” as opposed to living forever.

https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2019/05/20/if-god-is-dead-your-time-is-everything

The title (from Wood) is a misframing of Hagglund's position, it is not conditional on the existence or non-existence of gods. However the article is worth reading if you, as I was, are unfamiliar with Hagglund.

trev

(1,480 posts)It's similar to something I am myself currently writing. I should read his book.

procon

(15,805 posts)something that does not exist has any relevant impact on our lives.

Voltaire2

(15,017 posts)If you are referring to the title from the book review, yes the author of the review blundered.

Religion certainly has an impact on our lives, so oddly enough non-existent gods do impact us.

trev

(1,480 posts)are what the GOP is all about.

procon

(15,805 posts)allow the imagined existence of a supernatural being to affect their reason and intellect.

Voltaire2

(15,017 posts)Major Nikon

(36,915 posts)

Bretton Garcia

(970 posts)MineralMan

(148,180 posts)Those boundaries make our existence more precious to us. They make every moment, minute, hour, and all other measures of time crucially important.

Were it not for the short period of our individual existence, we would scarcely have any reason to accomplish anything.

That's this atheist's viewpoint.

trev

(1,480 posts)I like to think that, especially if we lived for millennia or even eternity, we would especially like to make that infinity of time as pleasant for ourselves as possible. We'd still want houses and comfortable beds and ready supplies of food and something with which to power everything. I can't imagine being willing to live forever as mere animals. I couldn't do it.

I'm also an atheist. But I recognize the human drive towards truth and some kind of meaning in the universe. That's the basic impulse underlying existentialist philosophy (which I subscribe to). I've been an existentialist since I was 17, and the past 50 years have been a search for meaning. I don't think I would lose that even if I lived on Earth forever.

The problem as I see it (and this may actually be what you meant) is that postulating an afterlife may dampen that search and its attendant drive to succeed and create. After all, if this life is merely a stepping stone to what is supposedly the purpose of existing, our "real" lives as it were, then there is no reason to put any stock in improving ourselves here and now. And if, in addition to this, we are going to be "forgiven" for our behavior here, then what is the point of improving that behavior? Looking at the actions of those who so believe, it is obvious to me that they think there is no such point. They exchange their humanity for angelic hopes, and in the process live the lives of devils.

Jim__

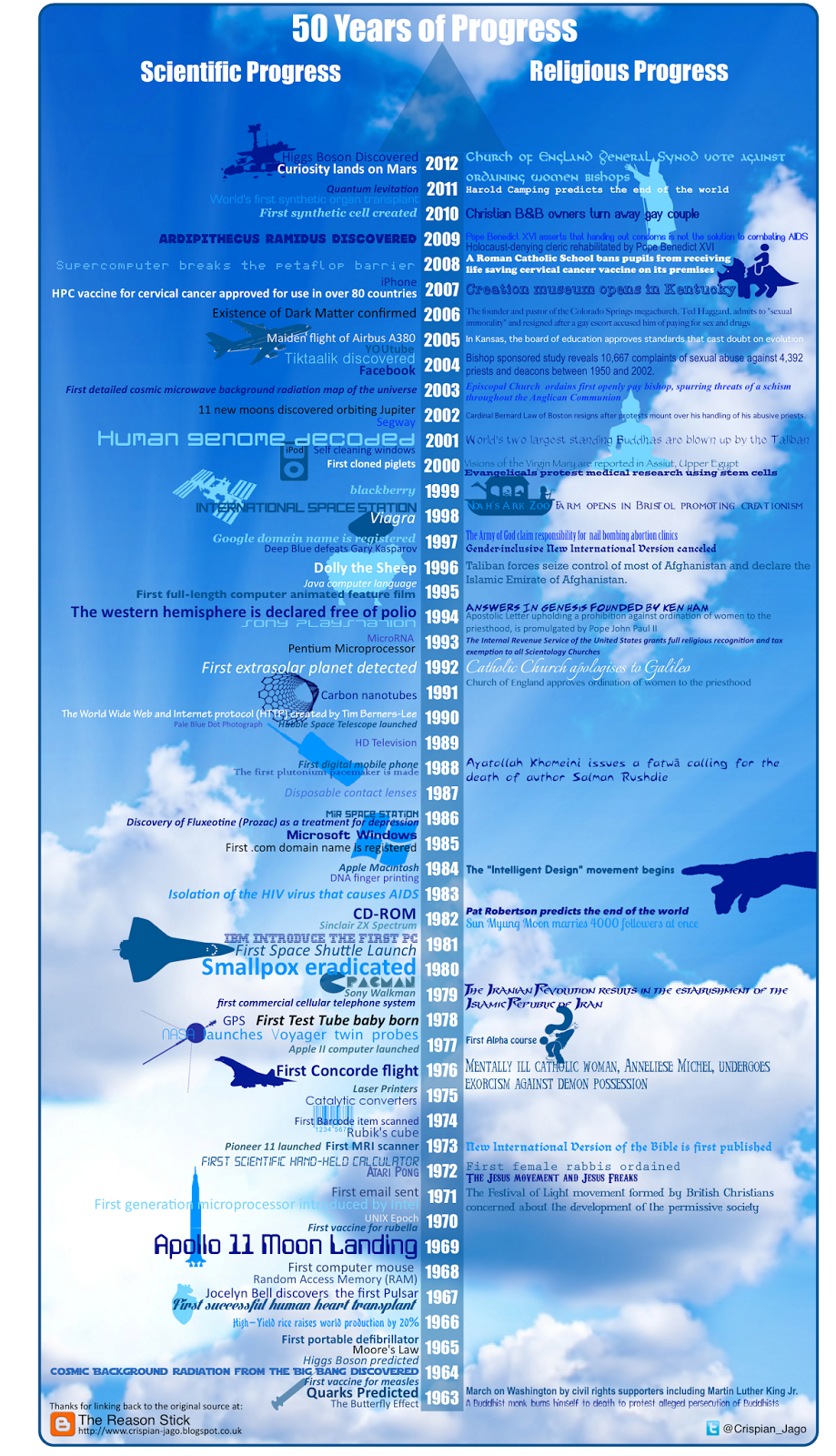

(14,544 posts)Her concern, and the concern of the other people in the discussion, seems to be more about the issues between religion and science over the last 40 to 50 years - unfortunately I don't find any specific question or concern that is being discussed outside of the generic arguing belief and unbelief. Montaigne is mentioned, but it is with the assumption that everyone around the table has read him. As far as I can tell, the full discussion from Salmagundi is available as Arguing Belief and Unbelief. With respect to the remarks from the citation in the OP: You die into Christ and thus into eternity, and life is just the antechamber to an everlasting realm that is far more wondrous than anything on earth; toward the end of the discussion David Steiner remarks that they had discussed religion for over two and a half hours, and no one had mentioned death. I will note that Robinson does use the phrase God is dead.

A brief excerpt:

We are, however, sharers in the dominant cultural myth even if we feel no reason to join in an angry faction in response to it. What we have long been educated to call modern culture has been based on the notion that, at last, we have the means to understand and explain the phenomena that awed and bewildered our ancestors. We have supposedly learned that the world is essentially simple—its apparent complexity only the compound of simplicities—and a construct that could be disassembled and read back to its origins. In fact, simplicity is nowhere to be found: not even in the smallest particles to which science has given inquiry any degree of access. Be that as it may, for some reason, the assumption of this unlimited capacity in humankind for understanding reality was to be felt, by us, as disillusionment and loss. The Renaissance gave us grounds for celebration in this voracious capacity for knowing. And yet the modernist interpretation was not, by any means, inevitable. Oddly, yet inevitably, when these same reductionist models that made our knowledge of reality a dull curse were brought to bear, they exposed an inner primitive with a snake’s brain.

This declension is often treated as the consequence of the great modern wars, but it predated them by decades and might, therefore, be more reasonably seen as cause than as effect. In any case, something dreadful has always been afoot among humankind, and something magnificent, as well. Of course, the same is true for us. But we have added an element of dullness and shrunken expectations, and in the face of all this, somehow, a posture of heroism was settled on—a heroism better dressed than most, but ready to bear the full weight of emptiness on its elegant shoulders. Of course, the whole construct is wrong. If there is one thing science has not done, it is dispel mystery. It has shown our thinking to be startlingly parochial, precisely in its assuming that by mere extrapolation—by leveraging what we thought we knew against what remained to be known—we would achieve an exhaustive understanding. We could have learned better—from Descartes, or Newton, or Locke—but the metaphysical elements in their thought are purged away in our reading of them, as if this most prescient and pregnant aspect of it were merely an odd convention. In fact, deep reality is of another mind than ours, just as these thinkers assumed it was. And we have known this for more than a hundred years—that is, for almost as long as we have been modern.

If there were a genuine interest, on the part of the new missionaries of atheism, in enhancing the public understanding of science, they would say that there is a deep, vast, fluent complexity in reality that precludes nothing at all—neither unexpressed dimensions nor multiple or parallel universes. It is by no means a closed system, nor can it be recruited to the support of any final statement about the nature of things. My own faith is inductive and intuitive, I suppose; in any case, it has been consistent through the whole of my life, poured into the cultural vessel of a particular religious and intellectual tradition which has engaged me for years and satisfied me very deeply. And this is no proof of anything. I do not recommend that anyone do more than follow whatever inkling she or he might have that existence would be a better experience minus this curious nostalgia for an old, illusory disillusionment. Baudelaire, Rimbaud, Nietzsche, Cioran, the schoolroom poets of disillusion, should be left to retire into their centuries as Pope and Dryden did into theirs.

much more ...

NeoGreen

(4,033 posts)..."issues between religion and science over the last 40 to 50 years", there are very few remaining, because science has "run the table" and won the debate. The anachronism known as 'religion' has lost. It is time to radically ablate this failed vestigial cultural construct.

It's not 'demons or devils" infecting the person, it's epilepsy, and it is treatable with out magic or incantations. Neuroscience and a rational approach to problems and challenges facing human beings saves the day, every time.

Voltaire2

(15,017 posts)“Science can’t answer everything therefore god” position. She also is either unfamiliar with what a sorry argument that is, or is hoping to pile enough verbiage on top of it to obscure the essential dishonesty. Given her quote in the article,and it’s transparent dishonesty, ...

MarvinGardens

(781 posts)I recently read "The Big Picture", by Sean Carroll. It's both a popular physics and metaphysics exposition. It's fairly recent. He summarizes a non-religious belief system (he calls it naturalism). Another one I found interesting, more physics than metaphysics, is "The End of Certainty" by Ilya Prigogine (Nobel laureate). The main points I took away from it are (1) thermodynamics can explain very complex systems, including life, and (2) determinism is false, and it is not merely a measurement problem.