Welcome to DU!

The truly grassroots left-of-center political community where regular people, not algorithms, drive the discussions and set the standards.

Join the community:

Create a free account

Support DU (and get rid of ads!):

Become a Star Member

Latest Breaking News

Editorials & Other Articles

General Discussion

The DU Lounge

All Forums

Issue Forums

Culture Forums

Alliance Forums

Region Forums

Support Forums

Help & Search

American History

In reply to the discussion: It's Constitution Day. On this day, September 17, 1787, the Constitution was signed. [View all]mahatmakanejeeves

(61,793 posts)1. The Constitution -- A Moveable Feast

It's Constitution Day. These days, you can see the Constitution in the National Archives, but it wasn't always there.

It used to be kept at the Library of Congress. That's where it was from 1921 until 1952.

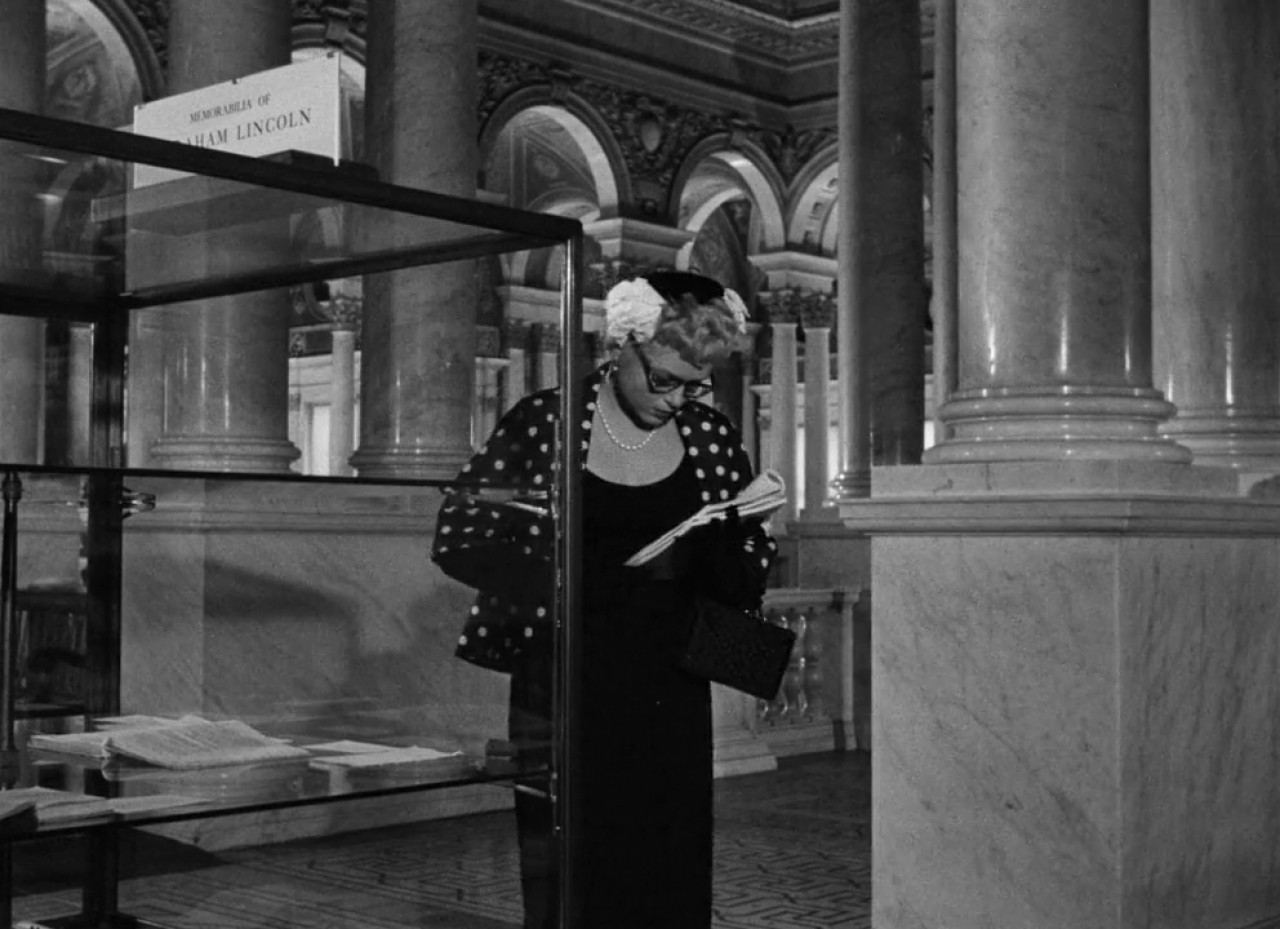

There's a Judy Holliday movie, "Born Yesterday," in which she and William Holden are seen at the Library of Congress viewing the Constitution. This is as close as I've been able to find:

Source: https://pureentertainmentpreservationsociety.wordpress.com/2019/06/21/film-fashion-fridays-9-judy-hollidays-black-dress-with-a-polka-dot-jacket-in-born-yesterday-from-1950/

Constitution of the United States—A History

{snip}

The Document Enshrined

The fate of the United States Constitution after its signing on September 17, 1787, can be contrasted sharply to the travels and physical abuse of America's other great parchment, the Declaration of Independence . As the Continental Congress, during the years of the revolutionary war, scurried from town to town, the rolled-up Declaration was carried along. After the formation of the new government under the Constitution, the one-page Declaration, eminently suited for display purposes, graced the walls of various government buildings in Washington, exposing it to prolonged damaging sunlight. It was also subjected to the work of early calligraphers responding to a demand for reproductions of the revered document. As any visitor to the National Archives can readily observe, the early treatment of the now barely legible Declaration took a disastrous toll. The Constitution, in excellent physical condition after more than 200 years, has enjoyed a more serene existence. By 1796 the Constitution was in the custody of the Department of State along with the Declaration and traveled with the federal government from New York to Philadelphia to Washington. Both documents were secretly moved to Leesburg, VA, before the imminent attack by the British on Washington in 1814. Following the war, the Constitution remained in the State Department while the Declaration continued its travels--to the Patent Office Building from 1841 to 1876, to Independence Hall in Philadelphia during the Centennial celebration, and back to Washington in 1877. On September 29, 1921, President Warren Harding issued an Executive order transferring the Constitution and the Declaration to the Library of Congress for preservation and exhibition. The next day Librarian of Congress Herbert Putnam, acting on authority of Secretary of State Charles Evans Hughes, carried the Constitution and the Declaration in a Model-T Ford truck to the library and placed them in his office safe until an appropriate exhibit area could be constructed. The documents were officially put on display at a ceremony in the library on February 28, 1924. On February 20, 1933, at the laying of the cornerstone of the future National Archives Building, President Herbert Hoover remarked, "There will be aggregated here the most sacred documents of our history--the originals of the Declaration of Independence and of the Constitution of the United States." The two documents however, were not immediately transferred to the Archives. During World War II both were moved from the library to Fort Knox for protection and returned to the library in 1944. It was not until successful negotiations were completed between Librarian of Congress Luther Evans and Archivist of the United States Wayne Grover that the transfer to the National Archives was finally accomplished by special direction of the Joint Congressional Committee on the Library.

On December 13, 1952, the Constitution and the Declaration were placed in helium-filled cases, enclosed in wooden crates, laid on mattresses in an armored Marine Corps personnel carrier, and escorted by ceremonial troops, two tanks, and four servicemen carrying submachine guns down Pennsylvania and Constitution avenues to the National Archives. Two days later, President Harry Truman declared at a formal ceremony in the Archives Exhibition Hall.

"We are engaged here today in a symbolic act. We are enshrining these documents for future ages. This magnificent hall has been constructed to exhibit them, and the vault beneath, that we have built to protect them, is as safe from destruction as anything that the wit of modern man can devise. All this is an honorable effort, based upon reverence for the great past, and our generation can take just pride in it."

{snip}

The Document Enshrined

The fate of the United States Constitution after its signing on September 17, 1787, can be contrasted sharply to the travels and physical abuse of America's other great parchment, the Declaration of Independence . As the Continental Congress, during the years of the revolutionary war, scurried from town to town, the rolled-up Declaration was carried along. After the formation of the new government under the Constitution, the one-page Declaration, eminently suited for display purposes, graced the walls of various government buildings in Washington, exposing it to prolonged damaging sunlight. It was also subjected to the work of early calligraphers responding to a demand for reproductions of the revered document. As any visitor to the National Archives can readily observe, the early treatment of the now barely legible Declaration took a disastrous toll. The Constitution, in excellent physical condition after more than 200 years, has enjoyed a more serene existence. By 1796 the Constitution was in the custody of the Department of State along with the Declaration and traveled with the federal government from New York to Philadelphia to Washington. Both documents were secretly moved to Leesburg, VA, before the imminent attack by the British on Washington in 1814. Following the war, the Constitution remained in the State Department while the Declaration continued its travels--to the Patent Office Building from 1841 to 1876, to Independence Hall in Philadelphia during the Centennial celebration, and back to Washington in 1877. On September 29, 1921, President Warren Harding issued an Executive order transferring the Constitution and the Declaration to the Library of Congress for preservation and exhibition. The next day Librarian of Congress Herbert Putnam, acting on authority of Secretary of State Charles Evans Hughes, carried the Constitution and the Declaration in a Model-T Ford truck to the library and placed them in his office safe until an appropriate exhibit area could be constructed. The documents were officially put on display at a ceremony in the library on February 28, 1924. On February 20, 1933, at the laying of the cornerstone of the future National Archives Building, President Herbert Hoover remarked, "There will be aggregated here the most sacred documents of our history--the originals of the Declaration of Independence and of the Constitution of the United States." The two documents however, were not immediately transferred to the Archives. During World War II both were moved from the library to Fort Knox for protection and returned to the library in 1944. It was not until successful negotiations were completed between Librarian of Congress Luther Evans and Archivist of the United States Wayne Grover that the transfer to the National Archives was finally accomplished by special direction of the Joint Congressional Committee on the Library.

On December 13, 1952, the Constitution and the Declaration were placed in helium-filled cases, enclosed in wooden crates, laid on mattresses in an armored Marine Corps personnel carrier, and escorted by ceremonial troops, two tanks, and four servicemen carrying submachine guns down Pennsylvania and Constitution avenues to the National Archives. Two days later, President Harry Truman declared at a formal ceremony in the Archives Exhibition Hall.

"We are engaged here today in a symbolic act. We are enshrining these documents for future ages. This magnificent hall has been constructed to exhibit them, and the vault beneath, that we have built to protect them, is as safe from destruction as anything that the wit of modern man can devise. All this is an honorable effort, based upon reverence for the great past, and our generation can take just pride in it."

Travels of the Charters of Freedom

Winter 2002, Vol. 34, No. 4

By Milton Gustafson

On December 13, 1952, the Declaration of Independence and the Constitution were transferred to the National Archives. (NARA, 64-NA-1-434)

View in National Archives Catalog

{snip}

Today, these documents are temporarily off display, receiving important conservation treatment, as the Rotunda of the National Archives Building undergoes a major renovation. When it reopens in September 2003, it will feature the Declaration of Independence, the Bill of Rights, and on permanent display for the first time, all four pages of the Constitution, as well as its Transmittal Page. All seven pages of the Charters will be placed in new state-of-the-art encasements that will preserve them for generations to come.

But where had these documents been before 1952? How were they preserved and handled from the time they were created until 1952? And why was the shrine in the Exhibition Hall of the National Archives Building, which was designed for the exhibit of these documents, empty for almost twenty years?

{snip}

The Declaration and Constitution, 1921 - 1952. From 1921 to 1952 the Declaration of Independence and the Constitution share a common history. In 1920 a committee of scholars investigated and made recommendations for the permanent preservation and possible exhibition of the Declaration and Constitution. A year later, acting upon the recommendation of Secretary of State Charles Evans Hughes, President Warren Harding signed an executive order transferring custody of the Declaration and Constitution from the State Department to the Library of Congress. The next day, Librarian of Congress Herbert Putnam went to the State Department, signed a receipt, placed the Declaration and Constitution on a pile of leather U.S. mail sacks and a cushion in a Model-T Ford truck, returned with them to the Library of Congress, and placed them in a safe in his office. Putnam asked Congress for a special appropriation to create a dignified exhibit so that visitors to Washington could view the documents in a "sort of shrine." Congress voted twelve thousand dollars, and the new exhibit opened in 1924. For the first time the Constitution was placed on exhibit, next to the Declaration, and newspapers reported that after almost 150 years of traveling the two great documents had finally found a permanent home.

But only two years later, Congress made its first appropriation for a National Archives Building. Groundbreaking was in 1931, and at the laying of the cornerstone on February 20, 1933, President Herbert Hoover announced that "the most sacred documents of our history— the originals of the Declaration of Independence and the Constitution of the United States" would be placed on display there. Later that year, architect John Russell Pope selected Barry Faulkner to create two large mural paintings for the Exhibition Hall, the subjects of which were to be those two great documents. The murals depict Thomas Jefferson presenting the Declaration of Independence to John Hancock and James Madison presenting the final draft of the Constitution to George Washington.

In 1934 President Franklin Roosevelt selected the first Archivist of the United States, R.D.W. Connor, and they both believed the Declaration and Constitution belonged in the new National Archives Building. When reporters asked, Connor declined comment but gave reporters a copy of Hoover's speech. Librarian Putnam declared that President Hoover "made a mistake." The two great documents were at the Library of Congress by executive order of the President and an act of Congress (the appropriation to build the exhibit), and they would remain there in their shrine instead of moving to the "lobby" of the National Archives Building. Connor was furious, but he remained silent. He owed his job to the recommendation of J. Franklin Jameson, chief of the Manuscript Division at the Library of Congress, and Connor had promised Jameson he would not take the initiative in seeking the transfer of the documents. Ironically, it was Jameson, the dean of American historians, who suggested the people to be included in the Faulkner's two great murals and approved his sketches. Privately, Connor talked to President Roosevelt several times about transferring the documents to the National Archives, but they agreed it would be best to wait until Putnam left the scene.

Then World War II intervened. In December 1941 the Library of Congress sent the Declaration and Constitution to the bullion depository at Fort Knox, Kentucky, for safekeeping. By September 1944 it was decided to return the documents to their permanent exhibit at the shrine in the Library of Congress. The new Archivist of the United States, Solon Buck, had no intention of pressing for their transfer to the National Archives. At one point he noted that the documents had been copiously cited in numerous scholarly works as being in the Library of Congress, and in case of their transfer, all those citations would be obsolete.

The Transfer. On September 17, 1951, there was a grand ceremony at the Library of Congress for the reopening of a permanent encasement for the Declaration and Constitution, newly sealed in helium by the Bureau of Standards. The distinguished guests included President Truman, Chief Justice of the United States Fred M. Vinson, members of Congress, plus a new Librarian of Congress, Luther Evans, and a new Archivist of the United States, Wayne Grover.

President Truman admitted that preserving the parchments might prove difficult, but the ideas in the Declaration of Independence and the Constitution of the United States would never perish and they would continue to give energy and hope to new generations here and in other countries. Truman also said the first ten amendments, the Bill of Rights, were just as fundamental a part of our basic law.

Truman then added a sentence, in his own distinctive handwriting, to the reading copy of his speech: "I hope these first ten amendments will be sealed up and placed alongside the original document. They are just as important."

While delivering his speech Truman slightly changed his own sentence. He said he hoped "the first ten amendments will be put on parchment and sealed up." And the Bill of Rights was not "just as important," but "the most important part of the Constitution."

It was all too much for Archivist Grover, who felt it was impossible to "go on indefinitely with ceremonies which gave the impression the documents would remain everlastingly the Library of Congress." Librarian Evans agreed with Grover. He later recalled running into Grover on the steps of the Library of Congress and telling him: "Wayne, the next ceremony for these documents will be when they are transferred to the National Archives."

And so, a few weeks later, Wayne Grover and Luther Evans met for lunch at the Cosmos Club and together hatched the plot to fulfill President Truman's request— to seal the Bill of Rights in helium and exhibit it alongside the Declaration of Independence and the Constitution, but in the National Archives Building.

How could they avoid controversy? Working together secretly, they agreed it would be necessary to clear the transfer formally with the President, congressional leaders, and Senator Theodore Green, the chairman of the Joint Committee on the Library. All favored the transfer. On April 30, 1952, Evans provided the agenda for the committee meeting, with the second item being "Transfer of certain documents to the National Archives." Evans went to the meeting alone because he knew that some of his colleagues at the library were hostile, and he wanted the committee not just to approve but to order him to transfer the documents, which it did unanimously. That led to seven months of remodeling of the National Archives Exhibition Hall and planning for the transfer.

The ceremony leaving the library on Saturday, December 13, 1952, was a spectacular event. The commanding general of the Air Force Headquarters Command formally received the documents at the Library of Congress at 11 a.m. Twelve members of the Armed Forces Special Police carried the six parchment documents, encased in helium-filled glass cases and enclosed in wooden crates, through a cordon of eighty-eight servicewomen down the library steps. The boxes were placed on mattresses in an armored Marine Corps personnel carrier. A color guard, ceremonial troops, the Army Band, the Air Force Drum and Bugle Corps, two light tanks, four servicemen carrying submachine guns, and a motorcycle escort paraded down Pennsylvania and Constitution Avenues to the Archives Building. Both sides of the street along the parade route were lined by Army, Navy, Coast Guard, Marine, and Air Force personnel. The general and the twelve special policemen arrived at the National Archives Building at 11:35 a.m., carried the crates up the steps, and formally delivered them into the custody of the Archivist of the United States.

President Truman and other dignitaries listen to Chief Justice Vinson delivering the closing remarks at the enshrining ceremony. (NARA, 64-NA-1-458)

View in National Archives Catalog

Two days later, at 10:15 a.m., on Monday, December 15, 1952, the formal enshrining ceremony was equally impressive. Officials of more than one hundred national civic, patriotic, religious, veterans, educational, business, and labor groups crowded into the Exhibition Hall. The chief justice of the United States presided. After the invocation by the chaplain of the Senate, the governor of Delaware (the first state to ratify the Constitution) called the roll of states in the order in which they ratified the Constitution or were admitted to the Union. As each state was called, a servicewoman carrying the state flag entered the Exhibition Hall and remained at attention in front of the display cases circling the hall. President Truman announced that "the Declaration of Independence, the Constitution, and the Bill of Rights are now assembled in one place for display and safekeeping." Senator Green briefly traced the history of the three documents, and then the Librarian of Congress and the Archivist of the United States jointly unveiled the shrine. Finally, Chief Justice Vinson spoke briefly; the chaplain of the House of Representatives gave the benediction; the United States Marine Corps Band played the Star-Spangled Banner; the President was escorted from the hall; the bearers of the flags of the forty-eight states marched out; and the ceremony was over.

Thus opened the new exhibit for these three parchment documents, together for the first time in one place and with a new collective name never before used: "the Charters of Freedom." Where did that phrase come from? Certainly we must give President Truman credit for first expressing the idea in 1951 of exhibiting the Bill of Rights with the Declaration and the Constitution. But the three documents did not become the Charters of Freedom until 1953, when the National Archives published The Charters of Freedom, an exhibit catalog that included facsimile copies of all seven parchment sheets.

In his speech, President Truman said "we are engaged here today in a symbolic act. We are enshrining these documents for future ages. . . . This magnificent hall has been constructed to exhibit them, and the vault beneath, that we have built to protect them, is as safe from destruction as anything that the wit of modern man can devise." Truman was right, but now the wit of modern man has devised something better— the new encasements, which will house the charters beginning September 17, 2003.

In these new encasements, the eighteenth century meets the twenty-first century. Sophisticated monitoring systems will allow conservators to periodically check the condition of the parchments, and the sealed cases will provide a stable environment. As the latest in the line of custodians of these documents, the National Archives and Records Administration is working to ensure that future generations will be able view them and be inspired by them.

Milton Gustafson is an archivist specializing in diplomatic records in the Textual Archives Services Division, National Archives and Records Administration. He joined the staff of the National Archives in 1967 and served as chief of the Diplomatic Branch, 1971 - 1988.

{snip}

Winter 2002, Vol. 34, No. 4

By Milton Gustafson

On December 13, 1952, the Declaration of Independence and the Constitution were transferred to the National Archives. (NARA, 64-NA-1-434)

View in National Archives Catalog

{snip}

Today, these documents are temporarily off display, receiving important conservation treatment, as the Rotunda of the National Archives Building undergoes a major renovation. When it reopens in September 2003, it will feature the Declaration of Independence, the Bill of Rights, and on permanent display for the first time, all four pages of the Constitution, as well as its Transmittal Page. All seven pages of the Charters will be placed in new state-of-the-art encasements that will preserve them for generations to come.

But where had these documents been before 1952? How were they preserved and handled from the time they were created until 1952? And why was the shrine in the Exhibition Hall of the National Archives Building, which was designed for the exhibit of these documents, empty for almost twenty years?

{snip}

The Declaration and Constitution, 1921 - 1952. From 1921 to 1952 the Declaration of Independence and the Constitution share a common history. In 1920 a committee of scholars investigated and made recommendations for the permanent preservation and possible exhibition of the Declaration and Constitution. A year later, acting upon the recommendation of Secretary of State Charles Evans Hughes, President Warren Harding signed an executive order transferring custody of the Declaration and Constitution from the State Department to the Library of Congress. The next day, Librarian of Congress Herbert Putnam went to the State Department, signed a receipt, placed the Declaration and Constitution on a pile of leather U.S. mail sacks and a cushion in a Model-T Ford truck, returned with them to the Library of Congress, and placed them in a safe in his office. Putnam asked Congress for a special appropriation to create a dignified exhibit so that visitors to Washington could view the documents in a "sort of shrine." Congress voted twelve thousand dollars, and the new exhibit opened in 1924. For the first time the Constitution was placed on exhibit, next to the Declaration, and newspapers reported that after almost 150 years of traveling the two great documents had finally found a permanent home.

But only two years later, Congress made its first appropriation for a National Archives Building. Groundbreaking was in 1931, and at the laying of the cornerstone on February 20, 1933, President Herbert Hoover announced that "the most sacred documents of our history— the originals of the Declaration of Independence and the Constitution of the United States" would be placed on display there. Later that year, architect John Russell Pope selected Barry Faulkner to create two large mural paintings for the Exhibition Hall, the subjects of which were to be those two great documents. The murals depict Thomas Jefferson presenting the Declaration of Independence to John Hancock and James Madison presenting the final draft of the Constitution to George Washington.

In 1934 President Franklin Roosevelt selected the first Archivist of the United States, R.D.W. Connor, and they both believed the Declaration and Constitution belonged in the new National Archives Building. When reporters asked, Connor declined comment but gave reporters a copy of Hoover's speech. Librarian Putnam declared that President Hoover "made a mistake." The two great documents were at the Library of Congress by executive order of the President and an act of Congress (the appropriation to build the exhibit), and they would remain there in their shrine instead of moving to the "lobby" of the National Archives Building. Connor was furious, but he remained silent. He owed his job to the recommendation of J. Franklin Jameson, chief of the Manuscript Division at the Library of Congress, and Connor had promised Jameson he would not take the initiative in seeking the transfer of the documents. Ironically, it was Jameson, the dean of American historians, who suggested the people to be included in the Faulkner's two great murals and approved his sketches. Privately, Connor talked to President Roosevelt several times about transferring the documents to the National Archives, but they agreed it would be best to wait until Putnam left the scene.

Then World War II intervened. In December 1941 the Library of Congress sent the Declaration and Constitution to the bullion depository at Fort Knox, Kentucky, for safekeeping. By September 1944 it was decided to return the documents to their permanent exhibit at the shrine in the Library of Congress. The new Archivist of the United States, Solon Buck, had no intention of pressing for their transfer to the National Archives. At one point he noted that the documents had been copiously cited in numerous scholarly works as being in the Library of Congress, and in case of their transfer, all those citations would be obsolete.

The Transfer. On September 17, 1951, there was a grand ceremony at the Library of Congress for the reopening of a permanent encasement for the Declaration and Constitution, newly sealed in helium by the Bureau of Standards. The distinguished guests included President Truman, Chief Justice of the United States Fred M. Vinson, members of Congress, plus a new Librarian of Congress, Luther Evans, and a new Archivist of the United States, Wayne Grover.

President Truman admitted that preserving the parchments might prove difficult, but the ideas in the Declaration of Independence and the Constitution of the United States would never perish and they would continue to give energy and hope to new generations here and in other countries. Truman also said the first ten amendments, the Bill of Rights, were just as fundamental a part of our basic law.

Truman then added a sentence, in his own distinctive handwriting, to the reading copy of his speech: "I hope these first ten amendments will be sealed up and placed alongside the original document. They are just as important."

While delivering his speech Truman slightly changed his own sentence. He said he hoped "the first ten amendments will be put on parchment and sealed up." And the Bill of Rights was not "just as important," but "the most important part of the Constitution."

It was all too much for Archivist Grover, who felt it was impossible to "go on indefinitely with ceremonies which gave the impression the documents would remain everlastingly the Library of Congress." Librarian Evans agreed with Grover. He later recalled running into Grover on the steps of the Library of Congress and telling him: "Wayne, the next ceremony for these documents will be when they are transferred to the National Archives."

And so, a few weeks later, Wayne Grover and Luther Evans met for lunch at the Cosmos Club and together hatched the plot to fulfill President Truman's request— to seal the Bill of Rights in helium and exhibit it alongside the Declaration of Independence and the Constitution, but in the National Archives Building.

How could they avoid controversy? Working together secretly, they agreed it would be necessary to clear the transfer formally with the President, congressional leaders, and Senator Theodore Green, the chairman of the Joint Committee on the Library. All favored the transfer. On April 30, 1952, Evans provided the agenda for the committee meeting, with the second item being "Transfer of certain documents to the National Archives." Evans went to the meeting alone because he knew that some of his colleagues at the library were hostile, and he wanted the committee not just to approve but to order him to transfer the documents, which it did unanimously. That led to seven months of remodeling of the National Archives Exhibition Hall and planning for the transfer.

The ceremony leaving the library on Saturday, December 13, 1952, was a spectacular event. The commanding general of the Air Force Headquarters Command formally received the documents at the Library of Congress at 11 a.m. Twelve members of the Armed Forces Special Police carried the six parchment documents, encased in helium-filled glass cases and enclosed in wooden crates, through a cordon of eighty-eight servicewomen down the library steps. The boxes were placed on mattresses in an armored Marine Corps personnel carrier. A color guard, ceremonial troops, the Army Band, the Air Force Drum and Bugle Corps, two light tanks, four servicemen carrying submachine guns, and a motorcycle escort paraded down Pennsylvania and Constitution Avenues to the Archives Building. Both sides of the street along the parade route were lined by Army, Navy, Coast Guard, Marine, and Air Force personnel. The general and the twelve special policemen arrived at the National Archives Building at 11:35 a.m., carried the crates up the steps, and formally delivered them into the custody of the Archivist of the United States.

President Truman and other dignitaries listen to Chief Justice Vinson delivering the closing remarks at the enshrining ceremony. (NARA, 64-NA-1-458)

View in National Archives Catalog

Two days later, at 10:15 a.m., on Monday, December 15, 1952, the formal enshrining ceremony was equally impressive. Officials of more than one hundred national civic, patriotic, religious, veterans, educational, business, and labor groups crowded into the Exhibition Hall. The chief justice of the United States presided. After the invocation by the chaplain of the Senate, the governor of Delaware (the first state to ratify the Constitution) called the roll of states in the order in which they ratified the Constitution or were admitted to the Union. As each state was called, a servicewoman carrying the state flag entered the Exhibition Hall and remained at attention in front of the display cases circling the hall. President Truman announced that "the Declaration of Independence, the Constitution, and the Bill of Rights are now assembled in one place for display and safekeeping." Senator Green briefly traced the history of the three documents, and then the Librarian of Congress and the Archivist of the United States jointly unveiled the shrine. Finally, Chief Justice Vinson spoke briefly; the chaplain of the House of Representatives gave the benediction; the United States Marine Corps Band played the Star-Spangled Banner; the President was escorted from the hall; the bearers of the flags of the forty-eight states marched out; and the ceremony was over.

Thus opened the new exhibit for these three parchment documents, together for the first time in one place and with a new collective name never before used: "the Charters of Freedom." Where did that phrase come from? Certainly we must give President Truman credit for first expressing the idea in 1951 of exhibiting the Bill of Rights with the Declaration and the Constitution. But the three documents did not become the Charters of Freedom until 1953, when the National Archives published The Charters of Freedom, an exhibit catalog that included facsimile copies of all seven parchment sheets.

In his speech, President Truman said "we are engaged here today in a symbolic act. We are enshrining these documents for future ages. . . . This magnificent hall has been constructed to exhibit them, and the vault beneath, that we have built to protect them, is as safe from destruction as anything that the wit of modern man can devise." Truman was right, but now the wit of modern man has devised something better— the new encasements, which will house the charters beginning September 17, 2003.

In these new encasements, the eighteenth century meets the twenty-first century. Sophisticated monitoring systems will allow conservators to periodically check the condition of the parchments, and the sealed cases will provide a stable environment. As the latest in the line of custodians of these documents, the National Archives and Records Administration is working to ensure that future generations will be able view them and be inspired by them.

Milton Gustafson is an archivist specializing in diplomatic records in the Textual Archives Services Division, National Archives and Records Administration. He joined the staff of the National Archives in 1967 and served as chief of the Diplomatic Branch, 1971 - 1988.

{snip}

Sun Sep 17, 2023: The Constitution -- A Moveable Feast

Sat Sep 17, 2022: The Constitution -- A Moveable Feast

Fri Sep 17, 2021: The Constitution -- A Moveable Feast

Thu Sep 17, 2020: The Constitution -- A Moveable Feast

Edit history

Please sign in to view edit histories.

Recommendations

0 members have recommended this reply (displayed in chronological order):

1 replies

= new reply since forum marked as read

Highlight:

NoneDon't highlight anything

5 newestHighlight 5 most recent replies

RecommendedHighlight replies with 5 or more recommendations

= new reply since forum marked as read

Highlight:

NoneDon't highlight anything

5 newestHighlight 5 most recent replies

RecommendedHighlight replies with 5 or more recommendations

It's Constitution Day. On this day, September 17, 1787, the Constitution was signed. [View all]

mahatmakanejeeves

Sep 2024

OP